A More Humane Way to Think About Productivity

Or: How I learned to Stop Worrying and Trust the Process

Tl;dr (via ChatGPT):

The author's past obsession with productivity, illustrated by their meticulous planning and execution of daily tasks since high school, led to a realization of its negative impact on their well-being, prompting a reevaluation of their approach.

Through research on the origins of productivity and its historical context, the author identifies flaws in the prevalent mindset that equates productivity solely with output and speed, emphasizing its detrimental effects on individuals.

The proposed alternative suggests reframing productivity as optimizing one's free time and deliberate choices, rather than focusing solely on completing tasks, advocating for a nuanced approach that prioritizes well-being and enjoyment of the process over compulsive task completion

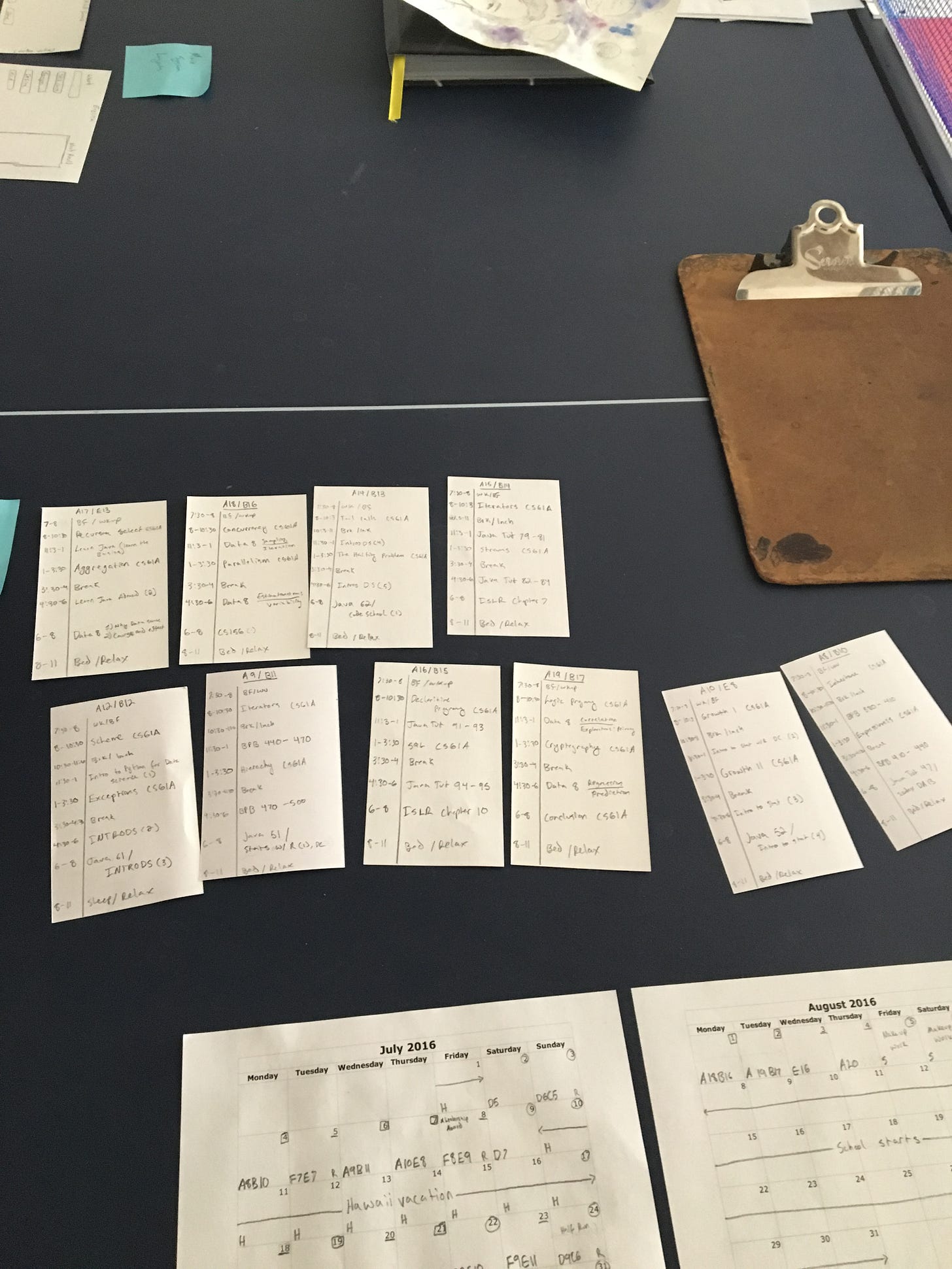

On the back of my letterman, embroidered in big white capital letters, is the quote: “Do you love life? Then don’t waste time, because time is life!” by Benjamin Franklin. I memorialized that special dictum because I lived and breathed it at the time. For the majority of my life, I’ve been obsessed with the idea of “being productive” - scrutinizing, maximizing, and optimizing every second of every day. That’s not hyperbole either, here’s a collection of notecards I made in high school detailing exactly what I planned to do every day for a month:

I made those cards every month, for years - and I followed them to a T as well! Looking back on them, I’m reminded of how much I let the anxiety of not Getting Things Done, of ‘wasting time’, control my life. In the past few years, I’ve begun to question and interrogate my relationship to ‘productivity’ in hopes of finding a healthier symbiosis.

I started by investigating the daily ‘productivity content’ I was consuming. At first, I found little wrong with this content which often pushed for knocking out to-do tasks at breakneck speeds, gritting through motivational droughts, and optimizing the most minute of workflows. After all, it seemed axiomatic that being productive meant getting more done in less time.

It wasn’t until I started researching the origins of ‘productivity’ that I began to see the flaws in that line of thinking. The word productivity comes from the Latin word “productivus”, which literally means “fit for production”. Originally, the word was used in a purely economic context, with some arguing its origins can be traced back to Adam Smith. Of course, our collective obsession with productivity didn’t ignite until the Industrial Revolution and the world wars, when rate-of-output was a life-or-death matter. Even though the need to be productive was arguably less perilous post-war, it didn’t matter; the match had been struck, and the fire that would spawn ‘McKensy Productivity Reports’ and ‘Harvard MBAs’ had been lit.

But I have no issue with any of that. It seems perfectly logical to me that companies should optimize for rate-of-output. Where I take issue, is when that mode of thinking is applied to individual, personal, productivity. You see, what I noticed after researching the origins of ‘productivity’ is how the ‘rate-of-output’ thinking that prevailed during its inception has largely followed into the realm of the individual. In contemporary productivity discourse, the prevailing sentiment you might find in online communities and blogs is often rooted in this output-first origin. It’s not always overt, but it’s almost always in the subtext.

Framing ‘being productive’ as a measure of how much you can ‘output’ (i.e., get done) per unit of time is flawed for a few reasons:

If all you care about is how many tasks you can knock off your todo list then you’ve lost the forest through the trees. The measure has become the goal and has thus ceased to be a good measure. Consequently, it can lead to an inappropriate prioritization of speed instead of quality. Some tasks should take longer than anticipated, some tasks need to be redone, or undone, or undone and then redone again. Failure to check an arbitrary box or move a card across a Kaban board does not imply you’re not productive.

Putting an overemphasis on maximal efficiency is overtly harmful at an individual level. It places unnecessary stress on the need to produce which can lead to everything from burnout to prolonged elevated levels of anxiety which can be detrimental to your health.

Instead, I argue, productivity should be geared towards optimizing your ‘free time’, i.e. the time for which you can choose what you’re doing.

An Alternative

Put another way, a productive individual would be someone who has a maximal amount of time that they can be deliberate with.

This isn’t an argument about quality vs speed. In this framing, productivity is merely a tool you employ to minimize the amount of time you think “I don’t need to be, don’t want to be, or shouldn’t be doing [x]”. It’s up to you to decide how you spend that time. For instance, you might need to write a lot of code in a short period of time in order to build some feature before a big launch. In this case, you are optimizing for ‘checking off a bunch of todo-list items’ which is perfectly fine because that’s how you’ve chosen to spend your time to meet some goal. Alternatively, you might have some very difficult problem you want to solve or some art piece you're working on. In this case, the ‘todo-list’ items are arbitrary enough to be unnecessary, but you can still employ productivity techniques to ensure you have as much time to work on the problem or art as possible.

The difference is subtle but important - the measure of your productivity revolves around how you spend your time (what you can control) vs how much you get done (not always in control). There is a correlation of course: the more of your time you spend on a task you want to complete, the higher the probability that you will complete it. However, failure to complete the task is not itself failure to be productive; rather, failure to make adequate time for the task is.

Implementation

So what does this look like in practice? Most of the techniques, tools, and processes would stay the same. The main difference is starting with a survey of your time before indiscriminately applying productivity techniques.

For instance, you might draw a diagram like this.

The blue slice would represent the amount of ‘free time’. Again, this free time could be spent working towards some goal, knocking off a bunch of small tasks, or playing video games. It’s up to you, the categorization is purely qualitative, ask yourself “is this what I want to be doing with my day”.

The red slice denotes all the time you spend doing “I don’t need to be, don’t want to be, or shouldn’t be doing”. I’ve sub-divided this category into 3 parts:

Reducible time - Time spent on something you don’t want to do that you could optimize by reducing.

Manual entry work that can be automated.

Typing the same commands over and over again to deploy something.

Time spent juggling calendar events or trying to stay organized.

Unwanted Distractions - Time you’d rather spend on something else but find yourself doing out of a compulsion or even addiction.

Time spent on social media.

Time spent playing video games.

Time spent going out drinking.

Irreducible time - Time spent on something you don’t want to do, but can’t reduce further.

Time spent on (unwanted) family obligations.

Time spent on civil duties - e.g., taxes.

Nonautomatable aspects of your job.

You could begin by categorizing how you spend your time on an average day into one of these categories. Then, you can begin systematically investigating different techniques to reduce the red slice. For instance, if you find yourself spending more time than you’d like on social media, then you might peruse r/nosurf for ways to minimize your usage. Or, if you’re feeling bogged down with meetings, you might use a tool to aid in your calendar organization.

Summary

What I’m proposing is more of a subtle change in thinking rather than a radical shift in practice. For me, thinking about my productivity this way has greatly improved my well-being. I still have a strong desire to get things done, but I no longer feel an intense anxiety to check-off every to do item on my todo list every day. Instead, I think consciously about how I spend my time and focus on enjoying the process rather than racing to finish something, trusting that naturally, the results will follow.